When an anomaly comes to seem more than just another puzzle of normal science, the transition to crisis and to extraordinary science has begun. The transition from normal to extraordinary research marks the prelude to a revolution.

(Thomas Kuhn, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions 1996, p. 82)

The neurodiversity movement is not political. It is scientific.

Here I want to explore a bit of the history behind why that’s the case and then propose a solution to how we can look at the brain—using a system dynamics approach—break this down, and discuss how this shift in perspective can provide practical means to better understand, assess, and support neurodivergent people.

The problem is viewing the brain as a machine

The core issue with how we understand the brain is that we’ve been viewing it mechanistically. When I say we talk about the brain mechanistically, I mean we tend to view it as a system that operates under fixed, predictable processes. It’s a model where the brain functions like a machine, following the same steps each time, influenced by external forces that can be manipulated and controlled. This has been the dominant way of thinking about the brain, but it doesn’t fully capture how the brain actually works.

Figure 1. Baddeley and Hitch's 1974 model of working memory proposed a multi-component system consisting of three parts: the central executive, which directs attention and coordinates tasks; the phonological loop, which handles verbal information; and the visuospatial sketchpad, which manages visual and spatial data. It assumes static, compartmentalised systems, overlooking the brain’s real-time adaptability and the dynamic interactions between cognitive functions. These are are essential for complex, integrated processing. The model has been widely influential and is still the basis of neuropsychological testing today. The model does not account for brain's fluid, interconnected processes.

The brain is not a machine. The brain is a self-organising complex dynamical system.

The brain cannot be broken down into simple, linear processes. The brain is constantly adapting and changing, influenced by a wide variety of internal and external factors, and it operates in ways that are more dynamic and less predictable than the mechanistic model allows. It is a complex dynamical system.

Figure 2. A simple system dynamical model of a cat population

In addition, it continually reorganises itself based on what is needed at any given moment in a dynamical manner. This is not a theory—the brain really is a self-organising complex dynamical system. That’s part of why creating consciousness in AI, for instance, presents a challenge. If we could create self-organising AI, that would be more like the way a brain functions (people are actually trying to do this). You can literally watch neurons doing this - moving around like little animals.

Because the brain is a self-organising complex dynamical system, the mechanistic models we’ve used to understand behaviour have certain limitations. These older models haven’t completely failed. They actually worked quite well, but only for certain types of people. Specifically, they’ve worked for people whose brains function in a way that fits into the existing models.

In other words, these models have worked for people whose brains appear to operate according to rules that align with what’s considered "expected" in terms of functioning. This is what the term neurotypical refers to—it describes brains that fall within the expected or average range of functioning on the bell curve within a given domain. This is also why I take issue with the term “neuronormative”—because it’s not just about what’s normative. It’s literally where someone’s brain falls on the spectrum of what’s considered average in a statistical sense. This then has the effect of creating what is perceived to be “normal”. And because humans like things to make sense, this extends to what is considered to be “good”.

The reason we struggle to understand neurodivergence is because we’re still using this outdated, mechanistic model to frame our understanding of the brain and behaviour, and this trickles down to psychology, including mental health treatment models.

This approach misses and misunderstands the complexity of all brains. It’s time to shift our perspective to a model that better reflects the reality of how the brain works. There is no logical reason why this cannot become the “new normal”.

So why are we so stuck?

We need to understand what incentivises people to uphold this way of thinking.

First of all, when I say “self-organising complex dynamical system” do you instantly feel a sense of deep understanding? Probably not. In fact, there are people trying to teach people how to think in systems - with the aim to improve the sciences. It is not familiar.

The mechanistic approach has been deeply ingrained in the science of psychology and cognition. It is what has generated modern, insurable psychotherapies. It has produced real-world scientific outcomes through validated cognitive models.

A paradigm shift

Newtonian physics was incredibly successful for centuries, explaining how objects move and how gravity works. Scientists eventually found limitations in this model, particularly when dealing with very high speeds and strong gravitational fields. Out of this emerged Einstein's theory of relativity, which gave us a more accurate and complete understanding of reality. It redefined space and time as interconnected and showed that gravity is the curvature of spacetime. While Newton’s model was useful and still applies in many everyday situations, relativity provides a more precise explanation of the universe.

We are in a similar position with our understanding of the brain in psychology. The mechanistic model has been useful, but it’s no longer enough to explain what we now know, especially when it comes to neurodivergence. We’re ready for a paradigm shift.

This isn’t about blaming people or accusing them of being intentionally ableist. There is no conspiracy.

Science progresses. We learn, and replace old models with new ones. There is ableism, of course, but it’s often a reflection of the outdated and ignorant ways we think about the brain rather than intentional harm (most of the time - people don’t like being wrong, and their defensive reactions can be distressing).

The mechanistic approach has genuinely been successful in explaining many behavioural, cognitive, emotional, and psychological phenomena. Given the success of mechanising the brain thus far, the models for psychology we’ve created are naturally based on this idea of "averageness." They focus on the mechanisms that enable functioning to remain within a particular range, with the assumption that this is the ideal. But like all approaches, there are limitations. The obvious problem is that there are many people whose brains don’t fall within this average range.

These limitations are why neurodivergent people are misunderstood.

The movement has needed to take on a political element because people have had to push for recognition and support through political means and advocacy, largely because the people in power haven’t been able to make those changes on their own. But this is not just about wanting liberty or demanding rights. It’s about the fact that the models we use to understand the brain simply -

do not apply well to neurodivergence.

So, I hope you can see that what we need is a new and better way to understand all brains, not just those that are easily defined by our existing limited models.

A new way to understand neurodivergence

I will now make a proposal that shifts the way we think about neurodivergence.

When we talk about neurodivergence, we often refer to traits, characteristics, deficits, or even just differences. I want to suggest a completely different way of thinking about neurodivergence that is more aligned with systems thinking.

Currently, when we assess neurodivergence, we use lists of symptoms for different disorders—like ADHD or Autism—and we compare them. We try to describe what traits belong to each. This is a mechanistic approach.

We are trying to be more neurodiversity-affirming, but are missing the point. Simply saying these characteristics are just different (and not bad), we’re still working within the assumption that there’s a way the brain should work (according to the mechanistic model). Again - the brain is not a machine. It cannot be divided into static parts.

So even though we are being “neuro-affirming”, we are STILL using this framework if we are describing neurodivergence by lists of traits with reference to what characteristics are and are not present, what is too much not enough, what is “really different” and what is not.

Instead of thinking about neurodivergence in terms of traits or deficits, we need to understand neurodivergence as differing along the lines of complexity and dynamism.

Neurodivergent brains have a heightened degree of complexity in the relationships between the brain’s parts and functions. This complexity gives rise to emergent properties—things we can’t predict or fully understand from just looking at the parts in isolation. If someone has complexity in their emotional, sensory, and cognitive processes—meaning the way these processes interact isn’t predictable or easily understood within our current models—this gives rise to emergent phenomenological experiences and observed reactions/ behaviours that are not easily understood. The point is that these emergent properties are not easily definable, as they emerge out of complexity. This is what characterises neurodivergence.

Dynamism refers to how flexible and changing the brain is. We can break this down into a few different areas, starting with temporality—how the brain handles information processing over time.

There are models that take a temporal approach, such as the diachronic theory of ADHD. In general, we haven’t emphasised temporality enough in understanding the brain. The focus has been on spatial resolution (the brain’s components as defined by what is circled by the person doing the study), which again, helps inform the brain’s operation within a mechanistic approach.

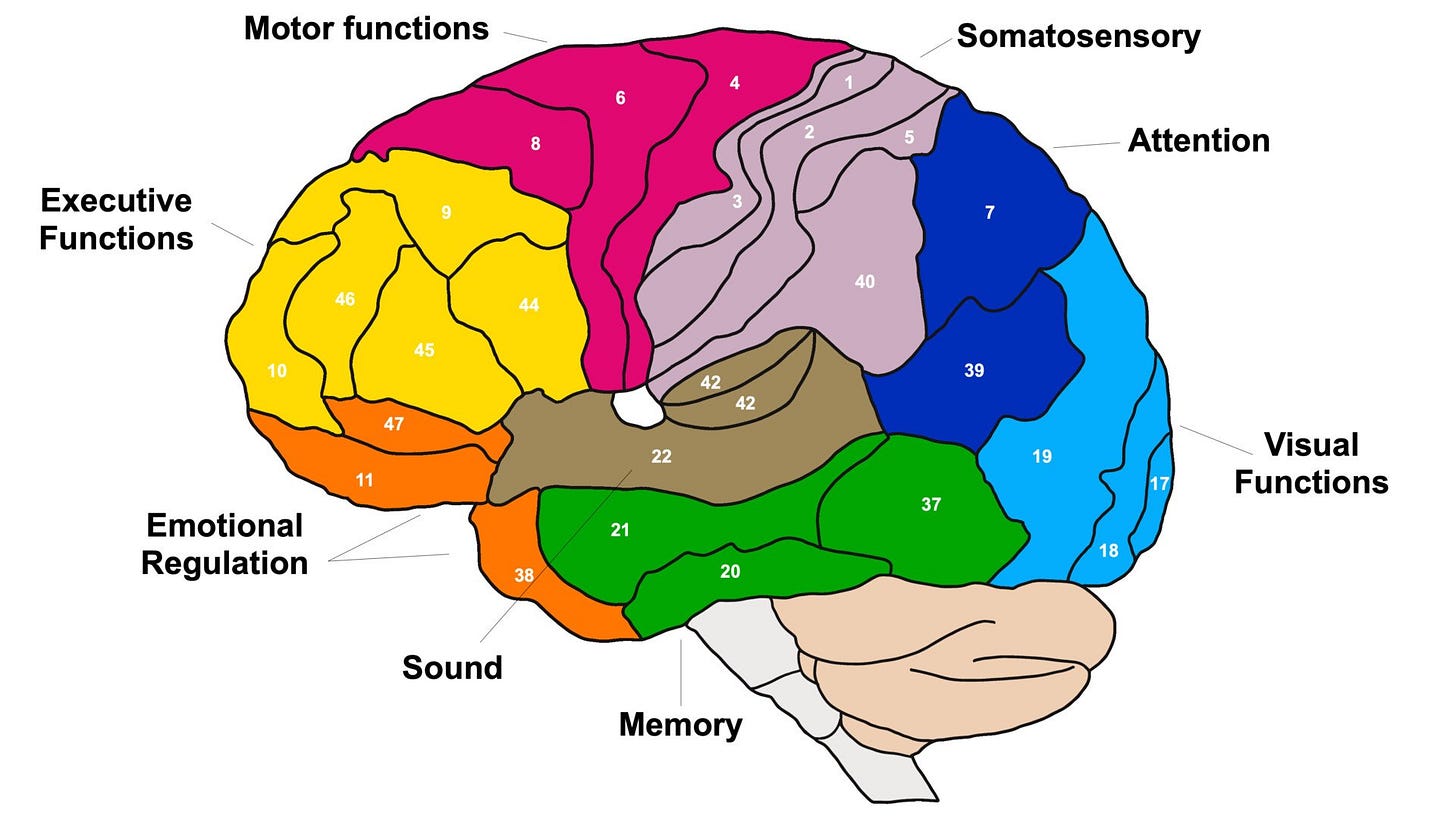

Figure 3. A Brodmann map. This is a way to spatially organise and divide the brain into 52 distinct areas based on differences in the cytoarchitecture—the cellular composition of the brain’s tissues. These areas correspond to different brain functions, such as motor control, sensory processing, and higher cognitive tasks. This it is just one of many methods to map the brain, focusing on structure rather than the brain’s dynamic and functional connectivity across regions. Created by Korbinian Brodmann in 1909

Considering temporal resolution—how the brain processes things over time—is just as important.

Figure 3. The brain's operational modules (highlighted in red) change over time, showing how these dynamic networks form, shift, and dissolve in relation to cognitive processing. Each snapshot represents a different time point, demonstrating how the modules self-organise into various functional networks, forming and dissolving in response to the brain’s requirements. The paper emphasises the brain's ability to achieve criticality—a balanced state between order and chaos—allowing for the emergence of consciousness. This approach highlights how neural networks interact dynamically, rather than being static, and how these interactions contribute to conscious experience. From Fingelkurts, A. A., Fingelkurts, A. A., & Neves, C. F. H. (2010). Consciousness as a phenomenon in the operational architectonics of brain organization: Criticality and self-organization considerations. Chaos, Solitons & Fractals, 44(1-3), 114-125

Understanding neurodivergence differing along the temporal dimension also ties into the theory of monotropism, which relates to ADHD and Autistic people a tendency focus more intensely on a single task or interest and difficulties transitioning between tasks or engaging in tasks within the expected level of intensity or duration.

The second aspect of dynamism is context specificity. This refers to the degree to which a brain’s functioning changes depending on the context, whether environmental or internal. Internal context could be things like mood or what one is thinking about. Brains that are highly context sensitive experience more change in response to different contexts. For example, some people are not very context-sensitive—their brain doesn’t change much based on what’s happening around them or inside them. Others, however, experience significant changes in how their brain operates depending on the context. So, the degree to which this happens is what I am referring to as context sensitivity.

To illustrate this, you could have someone who is not very context-sensitive, whose brain processes information temporally in ways that align with normative expectations, and whose complexity fits within what our current models understand. This is someone we’d call neurotypical.

There are already tools out there that can help us assess these aspects of brain function, and there’s no reason we couldn’t develop new ones. This could be a way to assess neurodivergence in terms of complexity, dynamism (temporality, and context sensitivity) rather than sticking to rigid diagnostic criteria based on traits or deficits.

Now, I’ll move on to how this framework could specifically apply to help address issues around twice exceptionality and giftedness.

Twice exceptionality as an artefact of the mechanistic model

As our current conceptualisations of neurodivergence are based on a mechanistic model, and this has produced what I’d call an artefact issue. It’s not a real issue, but it looks like one because this issue only emerges when we’re using models that don’t actually apply to the situation.

We have this strange phenomenon where someone is identified as having a disorder, such as Autism or ADHD, and at the same time, they are identified as being gifted and exceptional. This presents what seems like a contradiction, and people have tried to resolve it by using the label “twice-exceptional”. What happens here is that the person gets split into two parts: the issues and the giftedness. One part is seen as exceptionally bad (the disorder), and the other as exceptionally good (the giftedness).

The problem is that, for some people—not everyone, but for some—this split isn’t necessary or even accurate. (I do want to note some people have demonstratable impairments, like epilepsy, that can actually damage the brain and neurodegeneration. In cases like that, yes, you can say someone has a disorder and is also gifted). But for some, the problem arises due to the fact it’s the same underlying mechanism that causes both the Autism and the giftedness to emerge. It doesn’t make sense to call it twice-exceptional, because it’s not two separate things. It’s the same process. In some contexts or times, a person might show traits of Autism, and in other contexts or times, they might show traits of giftedness. So this idea of twice exceptionality isn’t consistent or coherent with what’s actually happening.

But the truth is, this contradiction only arises when we use a pathologising, mechanistic framework.

A shadow

Imagine you’re looking at someone’s shadow cast on a wall. From the shadow alone, you might think they are unusually tall and thin because the light is casting their shadow in a particular way, stretching it out. Without knowing it, you’re seeing a distorted version of the person—one that gives you useful (that there is a person) but incomplete information (that they are unusually tall and thin). Now, if you turn around and look at the person directly, you see the full picture in 3D: their actual height, shape, and other characteristics. It turns out that the shadow misrepresented the person.

Now, imagine that same person has a heightened sensitivity to their surroundings—they’re absorbing and reacting to far more sensory information than the average person. If we only see the “shadow” of their behaviour, like them being overwhelmed by loud noises or seeming withdrawn in a busy environment, we might interpret these traits as problematic or symptomatic of a disorder. This is the kind of shadow a mechanistic approach to neurodivergence gives us: it focuses on these sensory issues as deficits or challenges.

But if we turn around and look at the full picture—the person’s brain as a complex, dynamical system—we start to understand that those same sensory sensitivities aren’t just a source of overwhelm. They also allow the person to take in far more information than average, giving them a heightened perception of the world around them. This enhanced perception is often a characteristic we associate with giftedness. It relates to the ability to pick up on details, patterns, and nuances that others miss. The same mechanism that causes sensory overload can also be responsible for their ability to excel in certain areas, such as - in the right environment - taking in information that interacts to generate creative problem-solving or deep, abstract thinking.

The point is, the shadow misrepresents complexity by showing only showing one dimension in a concealed form - in my example struggles, like withdrawal or sensitivity—but when we see the whole picture, we can see the full resolution. We can see how in one person, the challenges related to Autism and their giftedness may not be separable and could be part of the same process. What looks like “exceptionally bad” in one context (sensory overload) is the flip side of “exceptionally good” (heightened perception and giftedness) in another.

This is why viewing neurodivergence through a mechanistic lens—just seeing the shadow—leads to confusion or contradictions, and how we have come up with the idea of twice-exceptionality. The same underlying mechanisms could explain both the giftedness and the challenges, depending on the context and how we frame them.

I want to make it clear, that I do not believe that what we are currently calling “Autism” and “giftedness” are the same thing. (to assume this would again assume I am doing mechanistic thinking, comparing and contrasting one list of traits with another, and assuming it is possible to stabilise “Autism” and “giftedness”). Both Autism and giftedness, as we understand them today, represent various complex processes that diverge from what is considered normal. The point is is that there are instances in which the same underlying mechanism (sensory sensitivity) generates differing emergent properties under different conditions. Of course, the processes possessed by the individual would interact with one another, too.

This is what we’re doing when we use symptom lists and checkboxes to diagnose neurodivergence.

Dimensionalising our understanding of neurodivergence

What I’m suggesting is that we shift our focus toward constructs that involve change over time, context, and interrelation. This way, we’re not simply evaluating a person’s behavioural success within a narrow window of what’s expected or "normal."

If we do this, it becomes much clearer that one individual can possess the ability to be gifted and also face significant challenges, and that this depends on their internal states and external environment. The context matters. It’s not about splitting someone into "issues" and "gifts"—it’s about recognising the complexity of the process that gives rise to these different dynamical characteristics that shift complexly depending on the context. We can define the person as possessing complexity and dynamism. Perhaps, “neurocomplexity” and “neurodynamism” may fit the bill.

We can still capture defined series of observations and label them—like we already do in psychology—but we have to recognise that these labels give us a limited perspective - like a shadow.

Labels

We are not there yet.

Whether or not people can fully embrace the level of complexity required to understand neurodivergence is still an open question.

Right now, we have particular labels, and these particular labels can serve as tickets to access support. They give us frameworks to conceptualise experiences, challenges, and capabilities. They help people build identities and find communities.

To take those labels away in order to replace them with something that’s more nuanced and eventually more useful will be part of a larger paradigm shift. The reason I’m raising this issue is because while we’ve identified the problem and its consequences, we haven’t yet landed on a full solution.

The solutions we have so far may be creating new problems as we go along.

My biggest concern right now comes from something my supervisor told me during mandated supervision, after I was reported to the Psychology Board for voicing concerns about the direction we’re heading in when it comes to helping neurodivergent people. I was told that when other neurodivergent professionals have advocated for a new approach to better understand diverse brains, they received feedback from the Psychology Board that the neurodiversity movement is a “cult.”

I refuse to let what I see as a huge opportunity for scientific progress, with real-world impacts on people’s lives, be reduced to identity politics. That is not what’s happening here. But that is what will happen if we don’t step up, get wiser, and provide a logical, evidence-based structure to prove that this new approach is better. We must challenge and disprove the outdated, reductionist understanding of neurodiversity that has been in place for decades.

So, I hope you’re with me. Let’s step into some complexity.

This is such an inspiring analytical piece and perspective and so insightful - thank you for your incredible work and for having the bravery to voice it.

I hope you will inspire a new, more constructive understanding of neurodivergence in the psychology and scientific field and that this will become a true movement, papaving the way for a much needed paradigm shift!